This is The Founders' List - audio versions of essays from technology’s most important leaders, selected by the founder community. This essay was written and published on Sep 9, 2019 by Scott Belsky, Founder of Behance. Read the full article on Medium here: https://marker.medium.com/creativity-is-the-new-productivity-d287d6ad7533

When leaders face the challenge of scaling their teams, they hire people to replicate many of the tasks they were doing. Sure, you might be able to do the mundane aspects of your job, but you’re better off hiring someone else to do it so you can concentrate on your more important value: thinking creatively and strategically about your product and company’s future.

In a sense, humanity has been doing the same thing for centuries: “hiring” people and machines to take over every mundane and repetitive action that consumes our natural human resources (work, energy, carbs — however you want to frame it). Sure, you could walk half a day to get your crop to market, but if a truck will get you there in half an hour, you’ll earn your revenue quicker and have more time to spend planting the next crop. From cars and industrial machinery to databases, algorithms, and office productivity tools, we have an insatiable desire to free our mental and physical energy for higher-order tasks.

Today, machines can accomplish a huge percentage of our daily tasks just as well as we can (if not better), and they do it for a lower price tag. Obviously, this has led to serious, negative ramifications for labor markets, but there is also upside. We are finally freed up — and disproportionately rewarded — for doing something only humans can do: be creative.

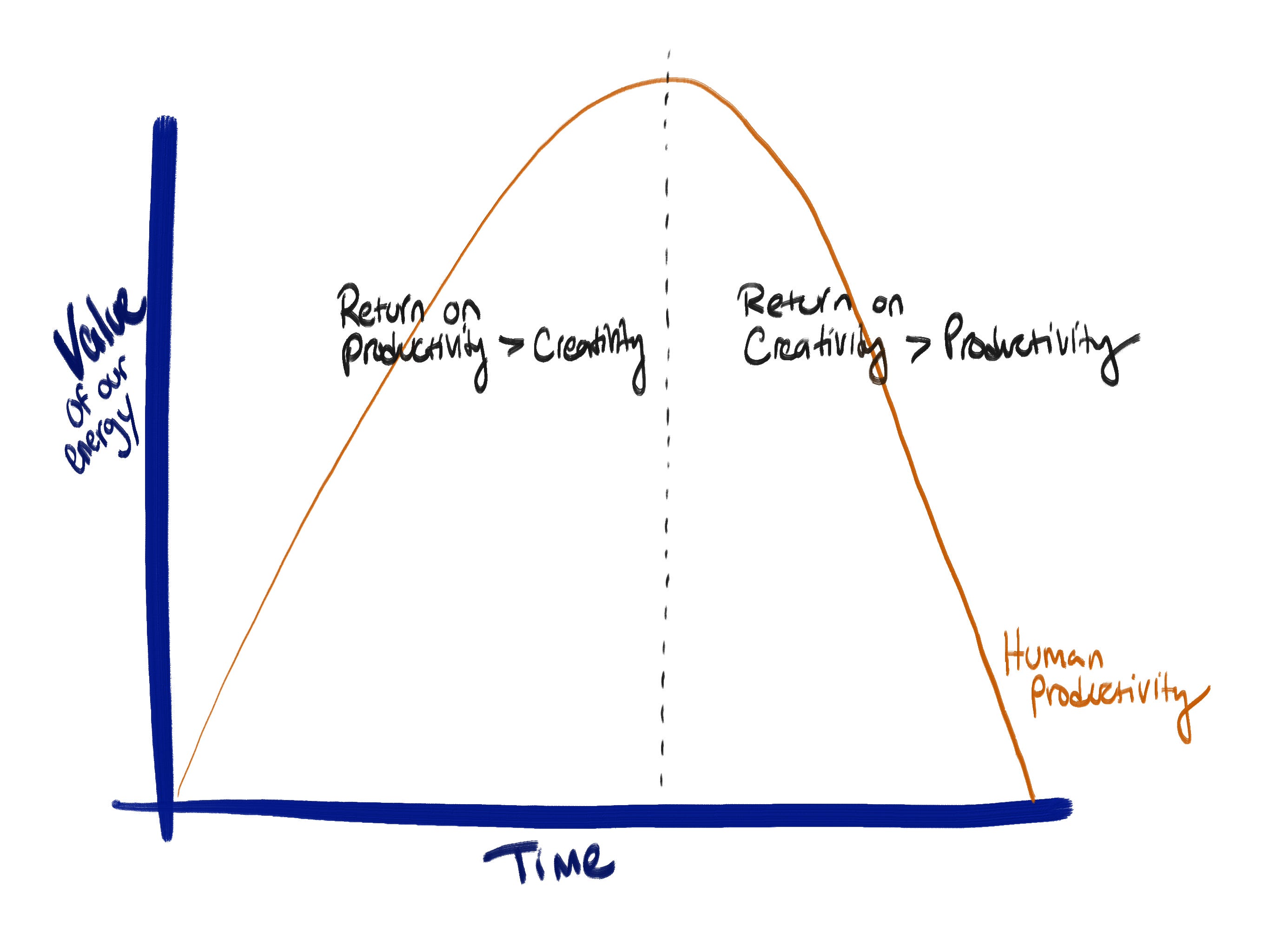

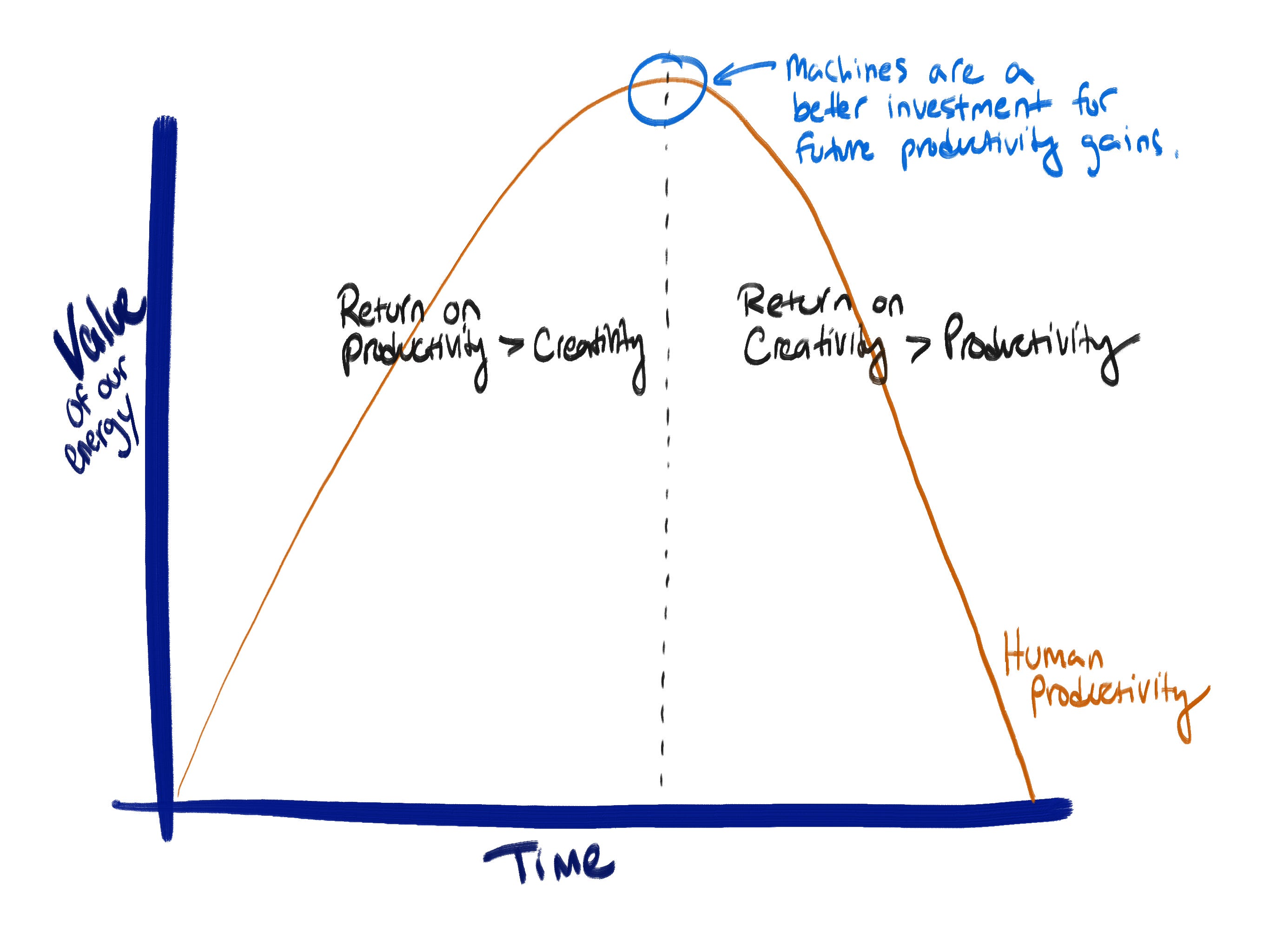

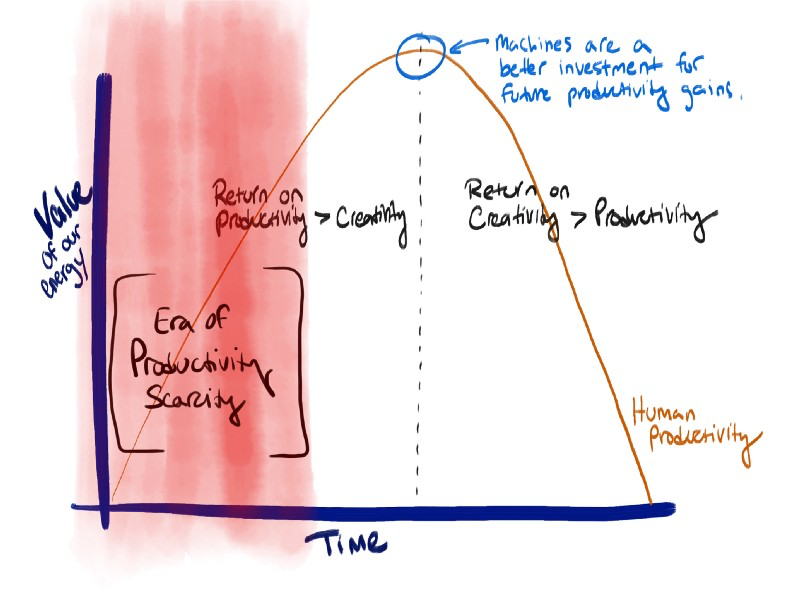

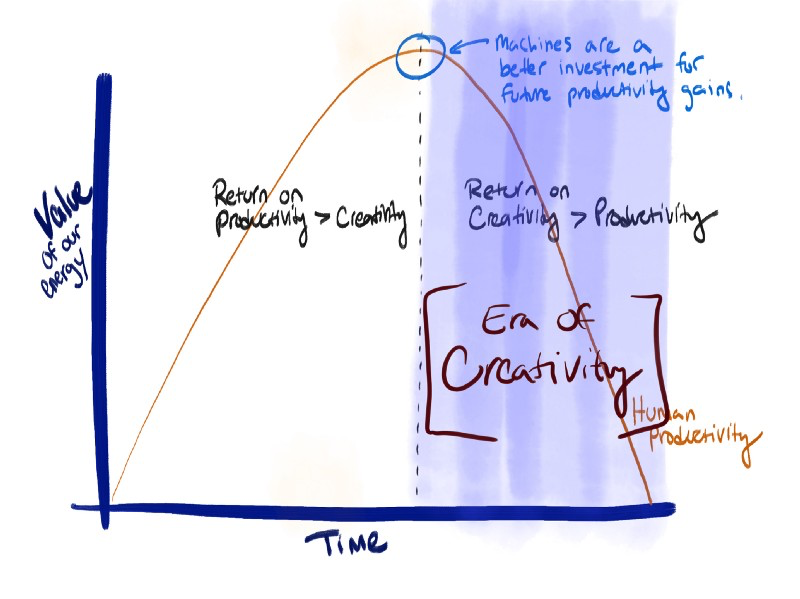

In the Human Productivity Parabola (see graph below), we have now passed the point — call it the “Productivity-Creativity Inversion” — where machines (algorithms, robots, etc.) have become a better investment for future productivity gains than humans. At this point, we as humans are better off spending our energy on creativity than on productivity.

Why the return of our human energy spent on creativity now exceeds the return spent on productivity. (Sketched in Adobe Fresco!)

If productivity, previously scarce and valuable, is increasingly abundant and commoditized, then we must shift our investments — from how we educate our children to how we plan our careers — to creativity, a truly scarce resource whose value is on the rise.

To better understand this shift, it helps to analyze its three phases: The Era of Productivity Scarcity, The Era of Productivity Abundance, and The Era of Creativity.

There’s a good reason parents traditionally shudder when their children tell them they want to be actors, painters, musicians or filmmakers. On average, pursuing a career in the arts has been a losing proposition compared to getting paid for performing tasks. A day job completing essential tasks, as menial as they may be, was a secure job.

During the Era of Productivity Scarcity, productivity improvements allowed us to skip some tasks, but only so we could perform other tasks. Every productivity tool the cavemen crafted or the IT department deployed simply accomplished more with less effort and freed human energy to focus on higher order productivity. When Excel automated calculations, it saved us time on a calculator, but we just used that time to gather more data. Human productivity remained the precious resource, and the easiest path to reward was to complete more tasks.

With the rise of technology and machines and algorithms of all kinds, we entered the Era of Productivity Abundance, in which the precious resource of productivity has been mined and manufactured with such tremendous (and, in some cases, ruthless) efficiency that its value has plummeted. In some ways, technology’s disruption of nearly every industry is a direct result of this new bounty of productivity that is disproportionately available to companies with technology at their center.

During this era, deploying machines and computers is a better bet for increasing productivity than hiring and training people. Industry by industry, the returns from human energy spent on productivity may still outperform what we spend on creativity, but at a declining amount.

This inflection, where human productivity is being devalued and repurposed as a result, has happened at different times for different industries. At the turn of the 20th century, no matter how fast a human could scurry down a street lighting gas lamps, they were inevitably going to lose that job when electric lights became available. Today, no matter how quickly you can sort and organize data in Excel, you’ll eventually be replaced by an algorithm that can do it cheaper and, eventually, better.

We are in the tail-end of this era, in which the smartest investment for improving productivity is always a machine or an algorithm.

This state of affairs can look like a dilemma — and for many people it will be. But it’s also an opportunity. As every industry reaches this point, the most rewarding path for individuals will be focusing on creativity. While productivity is about squeezing all the value out of existing resources, creativity and creative thinking are about discovering new resources: creative problem-solving that turns an obstacle into an advantage, inspiration that leads to a new product, creative reinvention that changes the course of your career.

The transition to the Era of Creativity will undoubtedly be difficult for some people, as all economic shifts are. But in the end, it’s a positive change for humankind. Being more productive can be satisfying, but ultimately it just makes you a more efficient cog in a faster machine. Being more creative, on the other hand, brings very different forms of fulfillment: joy, self-discovery, creative expression, new ways of doing old things, connection to others. In economic terms, GDP in this era will measure more than just raw economic output. It will measure happiness.

By no means is this shift happening across every industry at the same rate. I also recognize how few people in the world have the privilege or opportunity to pursue a solely creative career. However, this shift is real and has implications for the future of work, education, public policy, and technology. We need to be talking more about it.

Let’s explore a few of the ramifications.

Not too long ago, forging a lucrative career as a creative professional was a longshot. You needed to know the right people, work with the right agency, get discovered by the right scout, and work your way up the ladder, with nepotism as a headwind.

Even if you were lucky, you would seldom get attribution for your work. Big agencies and studios would take the credit and reap the new business that resulted from your brilliance. Your contributions would be largely obscured and, thus, commoditized. But everything is different now due to fundamental changes in distribution and attribution.

Distribution: While distribution was once severely limited and controlled by the agencies, studios, galleries, and record companies of the world, the floodgates have opened. It is now easy to distribute your work for exposure, for credit, and, at least some of the time, for pay. Yes, the democratization of distribution can drive down prices, but it yanks open the aperture of opportunity. If you produce content that connects with people, no corporation or institution can keep them from it. There’s always an avenue for distribution; and it’s not a given, but a possibility for the best content to earn the spotlight thanks to viral mechanics and social networks.

Attribution: With the help of image recognition, progressive policies for inclusion of work in portfolios (and portfolio networks like the one I started, Behance), and the “distributed agency” model, in which top creative talent is increasingly freelance, it is finally easy to determine who did what.

With these changes, we will have 100x — or maybe even 1,000,000x — as many artists, musicians, designers, craftspeople, jewelers, furniture makers…

But will there be enough demand to support such growth among creative professionals and everyday artisans? Take a look around at recent trends in consumer products, entertainment, and design. We’re starting to purchase more personalized “microbrand” goods as opposed to mainstream brands. We’re supporting more niche content targeted to specific audiences on platforms like Netflix. With networks like Pinterest for discovery, and marketplaces like Etsy, Soundcloud, Kickstarter, and Patreon for creative services, we’re starting to consume unique goods, music, and entertainment from a long tail of creators who are finally able to find their market. We’re even starting to engage deeply in extremely niche creative communities. Demand is tilting towards a larger creative workforce.

The opportunities in the Era of Creativity aren’t limited to creative professionals. Everyone wants to stand out. Whether at work, at school, or on social media, the simple image or video doesn’t cut it anymore. Office workers want better infographics and visuals to tell their story. Rather than just playing games and watching videos, the next generation of kids are creating videos on TikTok or building digital experiences in Fortnite. Every brand is publishing stories on Instagram and Snapchat that are crafted with unique fonts, colors, and other elements. Everyone is coming to realize that they have to be creative to outperform.

And new products are lining up to help them do it. In just the past few years, we have seen a surge of new applications and services, like Canva, Figma, Framer, Lightricks, PicsArt, and the list goes on. At Adobe, we’ve launched products like Spark and Photoshop Express that outfit non-professionals with powerful creative tools. And new marketplaces like the Custom Movement (a Y Combinator 2019 company), among others, are popping up allowing creatives to customize fashionable items like sneakers. We’re entering an age of modification and individuality like we’ve never seen before, and new companies to enable it.

Most people overlook one nuance about the rise of A.I.: Artificial intelligence actually makes creativity more viable and efficient. Creative professionals we survey at Adobe say they spend about half their time on tasks that don’t require creative inspiration at all — searching for the right stock photo, carefully applying a mask to an object, or removing a car from video footage. Artificial intelligence can take over these mundane tasks, saving creative pros time for more engaging — and lucrative — truly creative endeavors. And for the rest of us non-pros, artificial intelligence will help us find the right font, create designs with a sensibility for color and style we may lack, and translate or reformat our creations for different audiences and platforms automatically. So, while A.I. may replace many jobs, it also unlocks more creativity for professionals, as well as the masses.

For the last few decades, one of the greatest technology trends in big enterprise has been the broad deployment of productivity applications. From CRM software to PowerPoint and Outlook, these products, with their formulas, templates, group architecture, and permissions, were designed to make us more efficient.

As creativity becomes more important to both company and employee success, the most vital software will be the applications that help you be more creative. Already, we’re seeing product managers and executives using prototyping tools like Adobe XD and other experience design tools to “show vs. tell” their ideas, creating interactive models that have the ability to make conversations focused and productive. Social media marketers are using products like Spark and Canva to create eye-grabbing graphics when professional designers aren’t available. And your everyday office worker is reaching beyond PowerPoint to find the right graphic. Everyone wants to express themselves visually, and creative forms of leadership, debate, persuasion, and marketing are popping up in more and more places.

A shift as massive as the Era of Creativity inevitably raises lots of questions that we will have to address. The biggest ones on my mind:

None of these questions have easy answers. And there are many more to ask. But I’m incredibly optimistic about this next chapter in which we set aside our collective obsession with productivity, and allow our minds and imagination to breathe.