This is The Founders' List - audio versions of essays from technology’s most important leaders, selected by the founder community. "The 20s will see San Francisco face down some really big problems, and we’ll see if the city makes it out better or worse. But the wealth of social capital they’ve compounded will remain an undeniable asset to the tech community for a long time. " This is the audio version of Alex Danco's popular essay on Social Capital in Silicon Valley. Alex is currently head of Shopify Money and was a previous associate at Social Capital. Read the full article here - https://alexdanco.com/2020/01/23/social-capital-in-silicon-valley/

It’s January 2020. And if you’re a founder just starting out, trying to create something out of nothing, one of the best investments you can make is still a plane ticket to San Francisco.

A lot of people, including me, got this wrong when we looked forward to what the 20s would be like. All of the downsides of San Francisco and Silicon Valley as a global tech hub have more or less come true. It’s outrageously expensive; runways are shorter; there’s more competition for talent, narrative and oxygen. There’s no shortage of problems to work on, people to hire, or money in other cities.

But Silicon Valley still has this unbeatable advantage, available in abundance like nowhere else, that helps startups get off the ground: social capital. (I mean the general term “social capital” here, not the specific company Social Capital where I used to work.)

I’m continually surprised at how status and social capital in tech are simultaneously something we love to talk about, but also never want to talk about. We love to talk about individual examples of people acquiring influence creatively, or trendy virtue signalling that’s in fashion. But we don’t talk as much about the deep, systemic ways in which social capital makes the current tech industry possible in its current form at all.

When I wrote about angel investing and social status a couple months ago, it was interesting how much of the discussion was around, “this is right, but it’s not something we really talk about.” So let’s keep talking about it.

Social capital flows freely in Silicon Valley – if you ask for it the right way

Social capital is one of those terms I see people use generically to mean “community” or “status” or “good vibes”, but it has a specific meaning that’s worth understanding. It’s called social capital for a reason, because like other forms of capital, it works as a production factor. Just like a piece of capital equipment has value because it reduces friction, expense, or human labor of some kind, so do established norms, trust and relationships.

I got introduced to the concept of social capital from Robert Putnam’s book Bowling Alone. Social capital, as he presents it, is a form of wealth that can compound and throw off real dividends when it’s cultivated, or wither and die when it’s drawn down or neglected. Having access to social capital is a privilege. In the business world, social capital is earned over decades, and doled out carefully by those who have it: you can’t just give that stuff away.

Social capital is especially important if you’re trying to build something out of nothing, and need credibility and momentum in order to open doors and be taken seriously. Building startups outside of an established tech ecosystem is hard: there’s so much inertia and friction you have to fight that without existing momentum to draw from. You face a prohibitively steep climb out the gate.

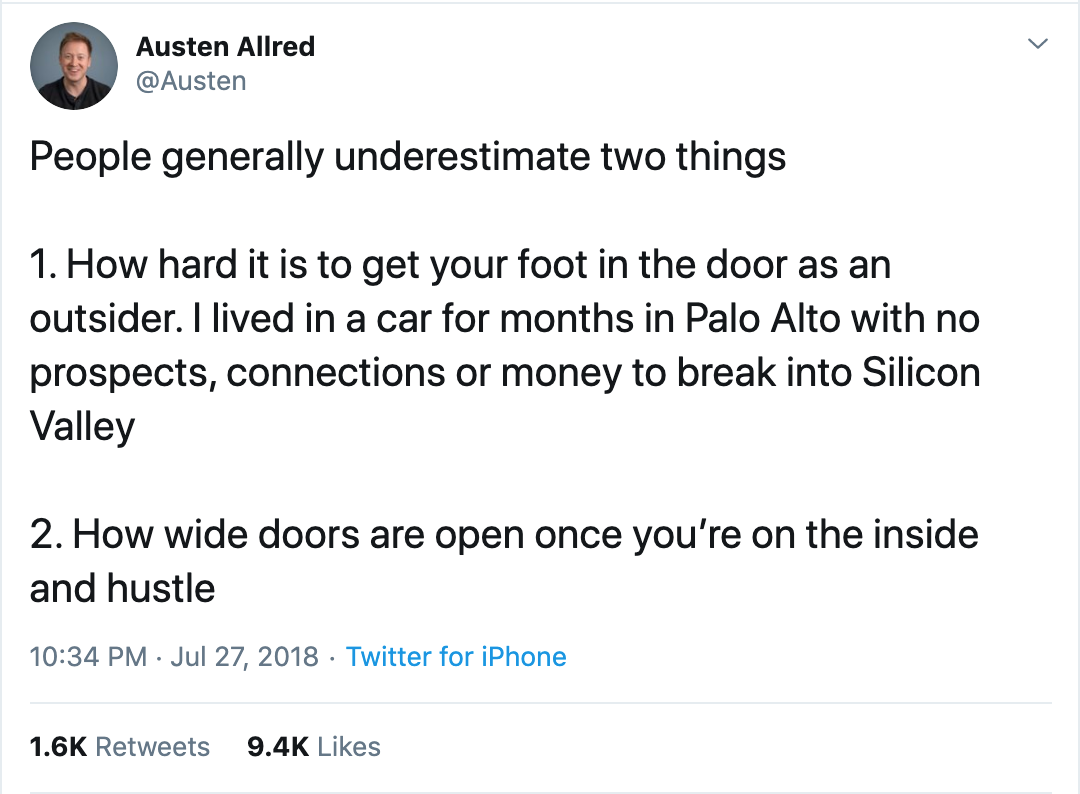

Meanwhile, it can be surprisingly easy for newcomers to tap into the social fabric of Silicon Valley and acquire that first bit of momentum, if you know how to ask for it. Those inertial barriers just aren’t there in the same way. People actually answer cold emails; people readily help out and make introductions; people will take you seriously. It’s a part of the culture. To some degree, people pay it forward because someone paid it forward to them. But it’s not just people being nice. Newcomers have real currency here. What, though?

Social capital is readily available to anyone, if, and this is a huge if, you know how to ask for it the right way. The magic password is simply asking, using the right language and demonstrating that you’re socially clued in to what’s going on: “Can I be in the group? I’m like you, almost.”

The Silicon Valley tech ecosystem is a world of pattern matching amidst uncertainty. We pattern match ideas, we pattern match companies, but most of all we pattern match people. If you are new, and you already speak the language and look the part well enough to be able to fit the pattern, but have just enough novelty and freshness to you that you don’t fit the pattern exactly, then people will be interested in you.

If you’re too different, you won’t fit the pattern at all, so people will ignore you. (Did I mention tech has diversity issues?) And if you’ve been in tech too long, you’ll fit the pattern too well, so people will also ignore you. But if you’re a newcomer who speaks the language? Then you’re interesting. You have “Goldilocks novelty”: a valuable form of social capital, which you can cash in immediately. You’re different enough to have unique potential, but similar enough to fluently use all of the leverage that the tech ecosystem offers you.

How else can you boost your social capital in Silicon Valley? Being a founder is obviously one way. Growth is also good at bestowing status – if you work at a fast-growing startup, even if it’s small or you’re not the founder, you’ll be in demand. Old fashioned charisma, being good at Twitter, or knowing good gossip obviously counts for something. You can also buy your way in by angel investing – so long as you do it the right way. Looking the part sure doesn’t hurt.

But really it’s about the basics: knowing the words for things; having some situational awareness about what people in tech have opinions about this week. Knowing what the pattens are, and how you fit. It sounds basic but it’s an essential part of signalling: I’d like to join the group, and I have something to offer.

The minute you acquire “in-group” status and establish a bit of social capital in Silicon Valley, everything about your career becomes easier. Introductions, advice, credibility and seed funding flow freely, hesitation and friction around new ideas goes away. It becomes easier to bootstrap something out of nothing, because you’re not starting with nothing anymore.

Social capital is distributed differently than conventional power

There’s a famous passage in War and Peace where a young lieutenant, Boris Dubretskoi, learns to navigate the “real system”, which supersedes the official system of influence and power in both the army and in society back at home:

When Boris entered the room, Prince Andrei was listening to an old general, wearing his decorations, who was reporting something to Prince Andrei, with an expression of soldierly servility on his purple face. “Alright. Please wait!” he said to the general, speaking in Russian with the French accent which he used when he spoke with contempt. The moment he noticed Boris he stopped listening to the general who trotted imploringly after him and begged to be heard, while Prince Andrei turned to Boris with a cheerful smile and a nod of the head.

Boris now clearly understood—what he had already guessed—that side by side with the system of discipline and subordination which were laid down in the Army Regulations, there existed a different and more real system—the system which compelled a tightly laced general with a purple face to wait respectfully for his turn while a mere captain like Prince Andrei chatted with a mere second lieutenant like Boris.

Boris decided at once that he would be guided not by the official system but by this other unwritten system.

You can imagine an identical scene playing out in San Francisco today. Substitute the purple-faced general with a Fortune 500 CEO, Prince Andrei with a VC, and Boris with a young founder with a small but fast-growing startup. In terms of actual real-world power and influence, it’s clear that the CEO has the most power, the VC significantly less, and the founder virtually none. But not in the unwritten system. In Silicon Valley society, you can easily imagine a scenario where the founder might have the most social capital in the room, and the CEO the least.

Social capital does not overlap exactly with conventional power or official status. If it did, then it wouldn’t be that useful. Social capital is interesting when it opens doors for people who don’t have power yet. It’s actually much more interesting than conventional power, because one is typically a leading indicator of success whereas the other is a lagging indicator. Potential value is far more interesting than value fully realized. Startups exploit that potential.

When working correctly, social capital helps resolve the chicken-and-egg problem of building something new. For a young founder in Silicon Valley, your social status is the most valuable thing you have: not only because it can open doors for you, but also because using your social status effectively is like a dress rehearsal for raising money and making deals. If you can demonstrate to early prospects and investors that you’re successfully able to promote hyped-up equity in your own reputation, it’s a good sign that you’ll be able to successfully sell hyped-up equity in your startup too. This is that special sort of magic quality that hangs around some founders like a halo. You instinctively know what they’re capable of, because at a social level, you’ve already seen them do it.

What’s interesting about this special quality, this “halo” of status and social capital, is that it’s not zero sum. It’s not like you’re born with it and either you have it or you don’t. Confidence is contagious. The more social capital there is in the community, the more status and credibility you can acquire as a newcomer, and the more you’ll want to bestow it on other people when it’s their turn. That’s the special feeling you get in Silicon Valley: it’s a place where social capital has compounded, uninterrupted, year after year, summer batch after winter batch.

After enough compounding, a paradox emerges: as people join the group who are all similar, but slightly different, the group accumulates more new ideas, and yet at the same time becomes increasingly self-similar. The tech scene becomes this growing, shifting mass of peers, all similar enough to one other that they reinforce and validate each others choices, and similar enough that everyone feels overwhelming pressure to perform: competition is everywhere.

The renewable energy source at the core of Silicon Valley, which drives everyone to work hard, comes from this tension: “I love you for being just like me, because it validates me. And I hate you for being just like me, because it makes us rivals.” The more you’ve bought into the group and benefited from its social capital, the more confidence you’ll feel for what you’re doing, but also the more pressure you’ll feel to not let your peers down.

Over time, social capital and conventional capital tend to converge. There is a controversial but widely practiced maxim in Silicon Valley that the original founding team and first few employees should be as similar to one another as possible: first, because you’re so fragile at that stage, any unnecessary friction will derail you; second, because what you’re doing is hard, and you need that peer-group tension to push through the early days.

These early founding and hiring decisions, where social capital matters more than anywhere else, make their lasting imprint through stock options. The wealth generated by a successful startup, which accrues disproportionately to its early members as opposed to its later ones, explicitly trickles down along social lines.

Social capital is antifragile: it’s either chaotic and growing, or orderly and shrinking

One of the big themes of War and Peace (which is the best book on social capital I’ve ever read, by a mile) is a phenomenon I don’t think there’s a name for, so I’m going to give it one: “Social Fog of War”.

Social Fog of War is a counterintuitive concept: in order for status- and social capital- driven social systems to work optimally, they must be opaque. You can have a sense for who’s at the top and who’s near the bottom; but the exact position and relative rank of anyone’s social status in the community should never be precisely knowable. Social Fog of War means you should never actually know, at any given moment, who is above or below whom.

Why is this so important? You can understand it intuitively with a little thought experiment, courtesy of Venkatesh Rao’s famous series The Gervais Principle. Imagine you’re in a group of ten people, and group membership is cool and desirable. You might have a sense of who’s the alpha of the group, who sets the tone for why the group is high-status. You might also have a sense of who’s at the bottom, and lucky to be there. But for everyone in the middle, their relative status is illegible: hard to say whether Alice is cooler than Bob, or whether they’re above or below average status.

If everyone suddenly became aware each other’s relative status, it’d be a social disaster: the group would collapse. The people on the bottom half will be made aware of their inferiority: they’ll feel self-conscious, like impostors. And the people in the top half will become aware of their superiority – they’ll feel pressure to break off from the group, which is obviously bringing them down. Ignorance was bliss.

The illegibility and opacity of intra-group status was doing something really important – it created space where everyone could belong. The light of day poisons the magic. It’s a delightful paradox: a group that exists to confer social status will fall apart the minute that relative status within the group is made explicit. There’s real social value in the ambiguity: the more there is, the more people can plausibly join, before it fractures into subgroups.

Silicon Valley is full of this sort of useful ambiguity. Things change so quickly, and status can get established and reassigned so unexpectedly, that Social Fog of War is thicker than normal. The big status-establishing moves, like building a unicorn or landing VC carry, take a long time – there’s a lag between what you’re doing and when it pays off, and all the while, your status will be indeterminate.

This embrace of ambiguity is best expressed in the tool that founders use to raise their first round: the convertible note. Part of the appeal of convertible notes is that, unlike a priced round, you only have to agree to a valuation cap. It lets your startup’s implied value sit comfortably and illegibly in a fuzzy range, rather than explicitly “higher than this comparable, but lower than that comparable.”

It works the other way, too. When the pref stack wipes out all the common in an acquisition, a lot of employees keep the halo of having worked for a company that exited for 500 million dollars. There are a lot of people walking around San Francisco right now whose peers believe they’re a lot richer than they really are. If the curtain suddenly got pulled back on a lot of these non-fortunes, it’d be a big problem! Social fog of war keeps things opaque, for the collective benefit.

Sar Haribhakti wrote a thoughtful blog post last year that pointed out something else: the brand name credentials in Silicon Valley rotate more quickly than they do elsewhere. On the east coast, it takes a decade for the default high-status credential to shift from working at an investment bank to working in management consulting to working for a fund. In SF, credential rotation happens much faster – every 2 years or so, instead of every 10. At face value, this is useful because it helps rotate out defaults at a healthier clip. But it’s helpful from a social fog of war perspective too. It’s useful that no one knows whose stock will rise next year.

This is a really good thing! It’s a lot harder to segregate people according to their credentials when the credentials themselves are constantly in flux, delayed by years, or otherwise uncertain. And when status is indeterminate, there’s more room for you to belong. Social Fog of War allows social capital and “in-group status” to scale to larger numbers of people. Silicon Valley is a place where status is a giant mystery box, and precisely because of that, it’s a place where social capital is available to the community in larger and more powerful quantities than elsewhere.

I don’t want to go full Taleb on this, but his concept of Antifragility is really applicable here. Social capital is antifragile: it thrives under conditions of disorder, and it suffers at rest. (This is a big lesson in War and Peace, by the way.) If it’s growing happily and chaotically, a group can continually accommodate new members without diluting the social capital of the group, so long as opacity is maintained. More disorder – in the form of rotating credentials, status illegibility, and a continual influx of new people – makes for more social capital, more collective confidence, and more communal benefits for those who share it. The thicker the Social Fog of War, the longer social capital will be able to compound uninterrupted, before splinter groups start breaking off.

But when status becomes more codified and explicit, then the social capital of the entire group gets threatened. Clarity and order tilt the game theory away from the communal group and towards less productive posturing and gatekeeping. This is why so many startup incubator programs, mentorship programs, and support networks fail so abysmally. The formal roles, titles and milestones that they impose, even if individually sensible, break the illegibility and inclusion.

The Golden Rule of Silicon Valley

You’ve heard me repeat this over and over, but I’m not going to stop: Silicon Valley works the way it does, as successfully as it does, because it has a rich social contract that governs everyone’s behaviour. Without that social contract, Silicon Valley tech becomes just another industry, or just another bubble.

One of the most important parts of the Silicon Valley social contract is the code of conduct around how you interact with people above or below your status level. There’s a kind of “Golden Rule” that’s in place if you participate in tech: “Treat others as if they might be the next great founder.” Status illegibility is a virtue.

This is where I really agree with what Michael Seibel was saying the other month (which prompted the angel investing and social status post) – the Bay Area is different because many more people have experienced upside regret. Hang around for enough time in the Bay Area, and at some point you will meet someone – although you won’t know it at the time – who goes on to do something wildly successful. If you brush them off, it’ll come back to haunt you. This will really make you pause, every time you meet with someone new for the first time, because this new person might be a special founder too. Since there’s a chance they might already be on a status rocket ship, you’d better treat them with that possibility in mind.

One overarching theme I’ve noticed over the past year or two is that explicit, codified status is coming to Silicon Valley. It’s not barging in and making a big fuss; it’s creeping in quietly. And it makes me a bit worried.

One way that explicit status is showing up these days is in the incessant virtue signalling, which used to be a harmless distraction but feels like something more than that now. It’s like members of the in-group, conscious that it’s getting crowded in here, feel the need to impose a bit of a tax, or a bit of a purity test, to see who exactly is “virtuous enough” to be really considered in the in group. Oh, you did 6 angel investments this year? That’ll score you some points. Resting heart rate below 50? Wrote some blog posts that hit all the right notes? Great. You can stay in. So long as you keep up the effort. Oh, you can’t make it 3x per week to the boxing gym? Sorry, no room for you in our group.

Another trend that’s a lot more explicit is the supposed rise in private group chats, where people say what they “really think”. Listen, I’m in some of these chats, and I promise you, they are not a new invention. They’re just exclusion, gossip, and pseudo-intellectual circle jerking. They are the opposite of punk. But they convey something worrisome, which is the idea that if you’re not in these invite-only chats, then you’re missing out on the real scene. (Sometimes I feel like the main point of these group chats is being able to announce, on Twitter, that you’re participating in them.) There’s nothing wrong with private conversations, but escalating social pressure to be “in” these conversations is another story.

Another trend that’s better intentioned but still suspicious to me is the increasing interest in “curation”, especially for people, that’s propping up everywhere in response to, “There are so many people in tech now and so many ideas; how can we make sure the best ideas and the best people can get discovered?” That’s a good goal, and to the extent that it actually promotes talented people who otherwise wouldn’t get recognized, then that’s great. But the other side of curation is exclusion, and the common basis for both of them is legibility: clearing out the fog, and shining the light of day on what’s out there. I can see why you might want this, but be careful what you wish for.

That being said, there’s also plenty of evidence that the state of social capital in Silicon Valley is stronger than ever. The recent Front Series C led by a bunch of individual enterprise software founders, for example, is just absolutely awesome. What a triumph of social capital in the ecosystem that individual people are willing to write cheques like this!

Expect to see a lot more of this, by the way. Startup founders and employees who are sitting on huge social capital reserves and paper stock option gains now have more options to reinvest their wealth back into the community immediately. People are figuring out that swapping their non-liquid equity for other founders’ non-liquid equity is a doubly good deal: it lets them diversify, and it multiplies their social capital with every reinvestment.

If this plays out the way it could, it could compound into yet another massive advantage for the Bay Area over other startup ecosystems, simply because you need a critical mass of people and social capital in one geographical location for it to work. The 20s will see San Francisco face down some really big problems, and we’ll see if the city makes it out better or worse. But the wealth of social capital they’ve compounded will remain an undeniable asset to the tech community for a long time.